October 1, 2018Thedreidel

The clatter of dishes as they’re being washed still puts Janie Scott in a tailspin. Her anxiety goes up, her heart starts pounding, and she has to leave the kitchen because the clink of metal reminds her of the sound the bullets made as they hit the festival ground pavement around her.

Oct. 1 marks one year since the Las Vegas massacre, in which a gunman perched in a hotel above a country music festival killed 58 people, wounded hundreds and linked more than 20,000 music fans together on a night that they will never forget.

It was the worst shooting in modern American history — and for those who survived, the last 12 months have been about finding a new normal, about building lives that can accommodate wheelchairs, flashbacks and a painful sense of fragility.

The last year has also involved watching the rest of the nation move on.

“Survivors have been forgotten,” said Ms. Scott, 42, a preschool teacher and mother of seven who has earned a reputation as the “mom” of a Vegas group she manages on Facebook. Concertgoers, she said, have become each other’s biggest support. “Because nobody else is doing it for us.”

Jennifer Campas was in her front yard in Whittier, Calif., on a recent evening when her son Leo left the house, slapping his flip-flops on the pavement.

“Ay, mi hijo!” she said, whipping around to find the source of the noise. “You scared me.”

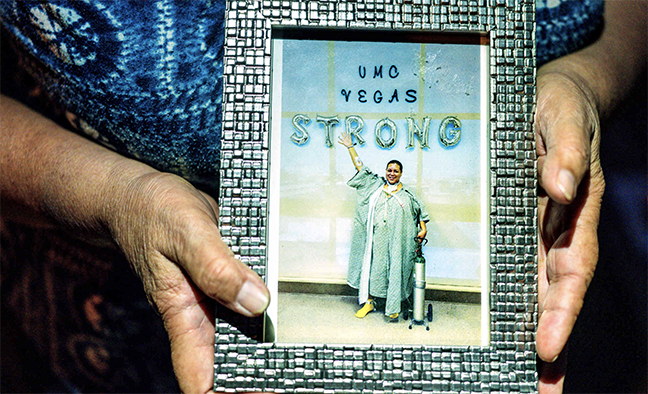

When the gunman opened fire last year, one of his bullets struck Ms. Campas, 41, in the forehead. When she woke from a coma, she had to learn to breathe again, to talk again, to walk again. She is now blind in one eye, and bullet fragments remain in her nose and neck. At night, she dreams about being shot.

She wears a single angel wing around her neck.

In May, she went back to work as the head nurse at an assisted living home. But she is slower now, less able to multitask. In her kitchen recently, she said she was thinking about stepping down and taking a lower position. Leo, 16, looked on.

“You know, I’m doubting myself,” she said. “And I don’t want to, I don’t want to be able to not carry it out, to fail. At this time in my life, do I really want to be so overwhelmed with work? I just kind of want to — maybe — live more.”

While the scale of the violence was unprecedented, detailed information on the hundreds of people who were wounded is not available in the official reports documenting the tragedy.

The New York Times reached out to Abraham Watkins, a law firm in Houston that is representing survivors, to understand the scale of the impact of the shooting on survivors. The firm described a range of injuries sustained by 50 victims who were wounded by the gunfire.

Of those 50 people …

20

were shot in the legs, arms or feet.

12

were shot in the torso, buttocks or spine.

2

were shot in the head.

Because the gunman used high-velocity bullets, many of the victims had small entrance wounds but tremendous internal damage or exit wounds.

“Normally your jaw is pretty resilient, but it just shatters like glass when it’s hit by a high-velocity bullet,” said Dr. Steven Saxe, a Las Vegas-based oral surgeon who treated seven patients after the shooting. “The actual injury only takes fractions of a second to occur, but it’s a lifetime of rehabilitation.”

At her home in Beaumont, Calif., Karen Smerber lifted her shirt to display the red scar running down her stomach, jagged as a map’s edge. “I’m the same size, technically,” she said. “I’m just not the same shape.”

Ms. Smerber, 48, a produce buyer at Stater Bros., was shot in the hip. The bullet pierced her intestine, and her husband, a retired fire captain named Matt, spent six weeks stuffing an incision in her side with gauze, then pulling out the infected material a few hours later.

“I don’t even know how he could still love me,” she said. “It was just something else, poor guy.”

Her stomach has taken on an uneven shape, and she feels like there is a hard shoe stuck inside. On her back patio, she winced as her dog leapt onto her lap and hit her stomach. It is difficult to sit, she said. She has started taking Zoloft, and she has returned to work part-time.

She can even line dance, a bit.

But the hardest thing is looking in the mirror. “My friends are so good,” she said. “They always reassure me that I’m beautiful and such. It’s just, people don’t realize that I feel bad about myself. And so then I feel — like with Matt — I feel disgusting most of the time.”

Nearly all of the 50 survivors documented by Abraham Watkins reported depression, anxiety, insomnia, fear of crowds and loud noises — hallmarks of post-traumatic stress disorder.

On a recent day, Dana Stout-Wilson, 54, stood on the blacktop at her middle school, her P.E. students in gym shorts in front of her. “Two laps, go!”

“These itch constantly,” she said, scratching at the purple bullet wounds on the back of her leg.

Ms. Wilson is back at work, the word “survivor” now inked on her arm. But the shooting is a perpetual shadow. She has nightmares; she is scared of sirens and helicopters.

The field where she teaches is a particular anxiety. It is frequently filled with children. It is also surrounded by hills and homes. She is constantly scanning for snipers.

The school is just miles from the 2015 shooting in San Bernardino, Calif., and already the staff has turned it into a fortress.

“You wonder when you’re going to be normal again,” she said. “I always feel like I’m going to break, like I’m going to fall apart.”

©2018 The Dreidel - All Rights Reserved